The blueprints there, right there, I‘ll tell the audience. If you want to do innovation and diversity and how they bolster each other, the blue print is 1994.

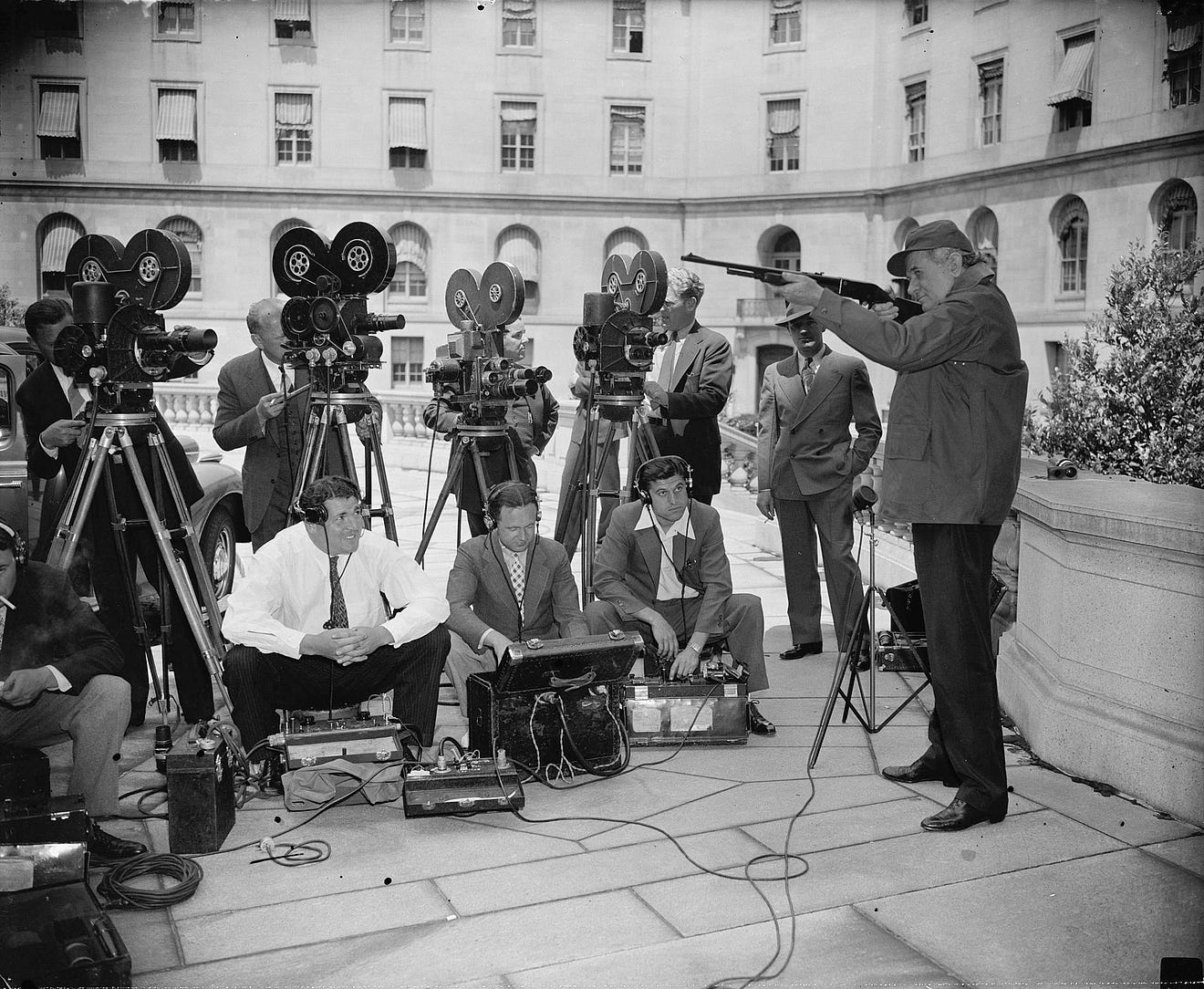

Back then 30 youngsters turned the British media upside down heralding the change we’re now living. Channel One TV was the UK’s first 24-hour cable news output for London. And another first, it was the pioneer of one-person broadcast units, referred to as videojournalism.

For a profession continuously grappling with how to do media representation, frustratingly, it’s been done, at least for its staffing of reporters. Its strategy was driven by its key management, the Fleet Street titan Sir David English (speaking below), the station’s team of Julian Aston, and Nick Pollard, and consultant Michael Rosenblum. (see fuller film at bottom of page).

Channel One thrived until advertisers squeezed their finance five years in, but as a revolution in media very little came close to it sense of innovation. These two clips, amongst many, from highly respected industry figures, set out that narrative.

As an incubator for talent and diversity it yielded Rav Vadgama, Award-winning Producer and videojournalist for Good Morning Britain; Dimitri Doganis, founder of Raw TV and recipient of many awards e.g. BAFTA; Trish Adudu, now a radio presenter and personality for BBC CWR, the BBC Local Radio service for Coventry and Warwickshire; and Rachel Ellison MBE, now a leading coach in leadership.

Channel One turned around my career following stints with BBC Newsnight, Reportage and the World Service covering South Africa and Pres. Mandela’s inauguration, but a permanent job appeared out of reach within established broadcasters, even with a testimonial from the UK’s leading think tank in International affairs.

New Journalism

Twenty seven years on, media legacies in diversity delivered by Channel One have atrophied. Its innovation was intrinsically linked to its diversity in what psychologists refer to as analogical thinking fermenting “external views”. It sowed a deep seed in many if its participants.

Many questioned journalism, news and story form. Steve Punter, one of the station’s stalwart videojournalists jokingly referred to the group as an assembly of unique different individuals that oddly shouldn’t work. It was the media equivalent of Marvel Avengers.

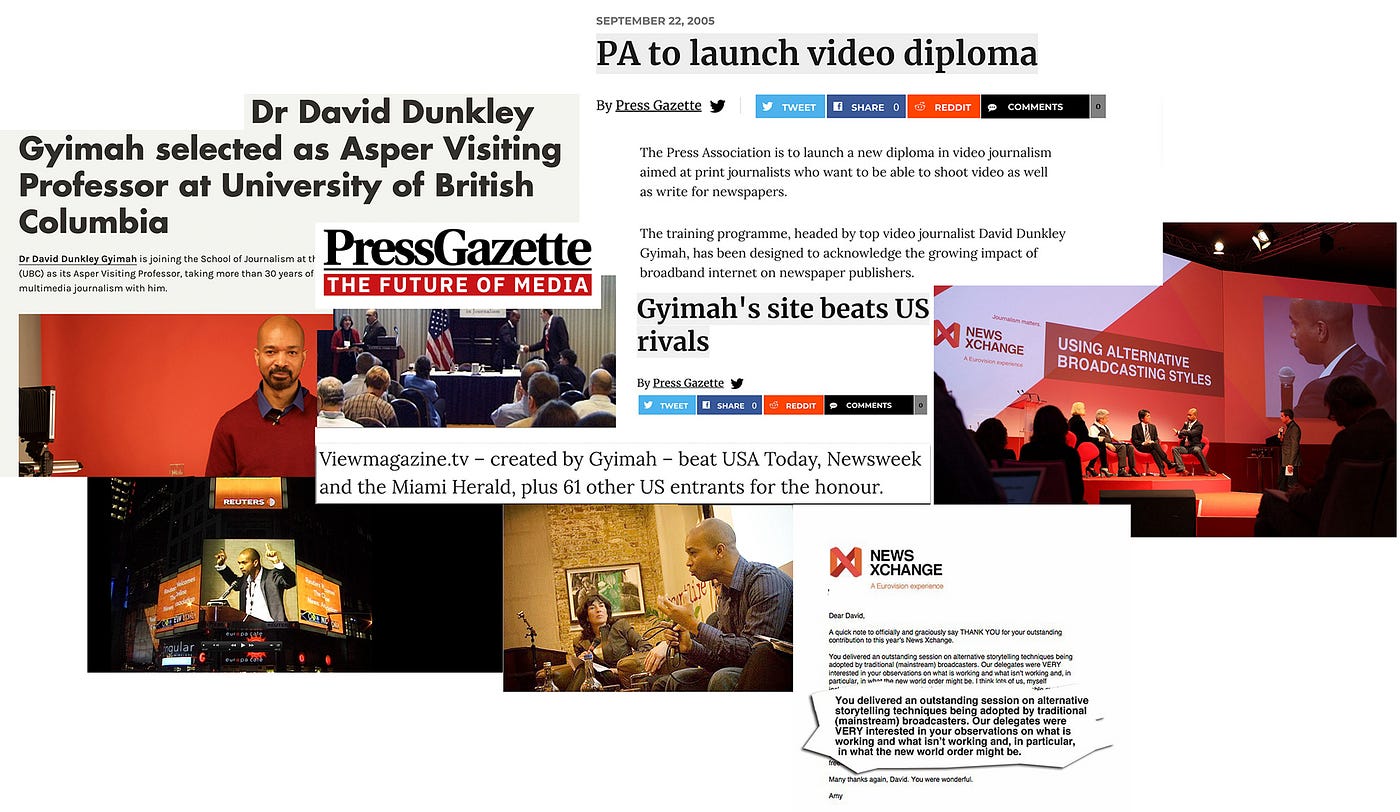

My head scratch would formally complete twenty years later, following hundreds of interviews and air miles, historical searches, training and debates in uncovering an inevitable form of journalism called Cinema Journalism. It would earn me a PhD and several industry awards.

From 2005 onwards with digital threatening traditional journalism practices I had the task of converting UK regional newspapers and the FT into new forms of videojournalists and platform encoders. Innovation and diversity too was key. It led to the good fortune of speaking at a fair number of conferences in the UK e.g. Apple and abroad (e.g. Russia) around journalism innovation and creativity, collaboration and diversity.

Journalism has been wrestling with several often intransigent and dynamic issues on different fronts, such as how to pay for journalism, how to master social platforms and reach new audiences, how to neuter disinformation and bad actors and how to keep the profession honest and hold power to account.

In person gatherings have been an ideal touch point to address these, bringing professionals together to share knowledge, tackle festering issues and build contacts.

Yet, as the end of the second decade drew near, there was a sense you could slide from one conference to another, meet familiar faces, and quite often observe recurring panelists and themes catering for the same-o, same-o. Sometimes it could feel like the conference equivalent of cabin fever — stasis; you’ve been here before.

The totemic events of 2019: COVID and the criminality against George Floyd amplifying a global movement in BLM were a “wake up call”.

A New Way of Conferencing

Within journalism, at least of the professional kind, whatever it was doing before 2019, coming out of it would be different. If you keep on doing what you’re doing, you’ll keep on getting what you get. Journalism was going to be re-birthed; its storytelling and philosophy captured in headlines required surgery, its actors needed widening. Things couldn’t continue as normal.

My first in-person event courtesy of the Society of Editors (SoE) leaves me cautiously hopeful. I had just recently finished working as an advisory board member for the British Library’s major exhibition: Breaking the News: 500 Years of News in Britain, as well as contributing a chapter to their book on Black Lives Matter and the language of News.

A kindly email following on from the exhibition would reach me explaining how the SoE’s conference might be of interest. The title Future of News has been a popular one that often proves hugely attractive. Two years ago I chaired a 250 delegate conference on the subject. It would be attractive again.

SoEs lineup, not exhaustive here, was something to admire: Keynoter Ros Atkins, the BBC man who has single handedly revolutionised journalism and explainers; leading figures from the BBC and Telegraph and RTS winner Warren Nettleford of Need to know debated the future of news chaired by Kamal Ahmed, Editor in Chief of The News Movement.

Changing the newsroom featured a panel with Guardian executive Joseph Harker; seasoned war correspondents lent their expertise to the Ukraine war coverage. It was foregrounded by a poignant silence for fallen journalists. Then Alok Sharma MP closed the event with Cop26 in his rear view mirror whilst applauding the robustness of the press.

Yet, there’s a question worth grappling with. Post Floyd and COVID what new role, if any, should conferences be playing in journalism education? How different should they be from their predecessors? Is is a question of greater diverse and targeted programming within the decision makers? Is there a new function for the circuit of conferences from professional bodies yet to be acknowledged?

SoE’s conference placed diversity as an integral conversation in Changing the Newsroom. Harker emphasised the need for an action, rather than an aspiration, and even that. He addressed what he called the elephant in the room, and few would deny it, asking why the SoE took six months to apologise for their position that racism did not exist in the British press.

If, as it’s widely recognised, journalism (not a homogenous discipline) needs to have emerged from the last two years with greater introspection and reflection several custodians are well placed to deliver on this. The SoE remains one of the UK’s most influential journalism bodies and a look at their virtual conference page displays a raft of initiatives.

Conference to dos

Myfirst in-person has me in reflective mood as I think to the several conferences now opening up and how they might build post 2019?

- Ensuring the growing unease of what was wrong in journalism does not dissipate. This requires concretising new visions and memories in ways that shift thinking. Work at the British Library and as an artist-in-residence at the Southbank Centre typified this sort of brief. Storytelling always circles around culture, but because of how it crystallised as News many years ago in largely homogenous cultures, cultural framing has rarely acquired the prominence in journalism as objectivity or impartiality. It should.

- Increasing diversity of speakers on all panels and ensuring people of colour are not solely invited to conferences to speak exclusively on race and culture sessions. Nettleford and Nabihah Parker speaking at the SoE on innovation was refreshing. Equally, on a spectrum of issues poignant to older audiences the Black and brown frozen middle should be welcomed.

- Actioning targeted conference talking points and procuring commitments or pledges from execs. At the SoE event panelists agreeing to visit universities to share knowledge was one. Inviting senior execs to agree to material change in say hiring diverse staff could be one of many others.

- Physically build the future. In a recent post on this platform I ask why a new wing of solutions journalism, solutions media, shouldn’t engage in physical builds, for instance engineering apps (see here). Media, remember, has no natural borders. If there’s a sense of what’s wrong why not engineer alt solutions.

- Facilitating exchange hubs, so delegates can find one another to swap ideas. The usual route is after drinks, but I’ve often found they can be hit and miss. I had a highly entertaining conversation with a delegate which emerged serendipitously only when she spoke ( off subject) about Brit School, and I segued into my son Robert who appeared on BBC Young Dancer.

- Leverage conference talking points via active use of social media and post conference reports, targeting ( Hashtag) specific groups. Greater interactions with universities and students would facilitate this. There’s an integrated debated between academia and the practice of journalism that is yearning to be reshaped.

Short film by David Dunkley Gyimah called The Thirty — pioneers of British Media

About the author

Dr David Dunkley Gyimah is recognised as an international journalism innovator and expert in media and international affairs. A chemistry and maths graduate turned journalist and creative producer his career spans thirty plus years combining media and academia. He’s worked or presented for a number of outfits and international brands e.g. Channel 4 News, Apple etc and continues to consult for major companies. A former Artist in Residence at the Southbank Centre, he’s the first Brit to with the (US) coveted Knight Batten Award for Innovation in Journalism. On Medium he’s designated one of their top writers in journalism, amongst 28k writers posting 68k stories. He’s based at Cardiff University.