Bent over the kitchen sink washing dishes (the washing machine has packed up) my mind drifts. Curse shingles. I now have a renewed healthy respect for work-life balance. Just how does one make a change?

I also dwell on that question. What did happen post the aftermath of last year’s BLM moment? Just how were the incredible array of stories that surfaced to address racial issues curated so they become everlasting epistemologies for future generations?

And then glaring through the floor as if I have Superman X-ray eyes, I think back to the tapes in my garage that have gathered dust for thirty years? Could I finally muster the energy to do something with them? And if so what purpose would they serve?

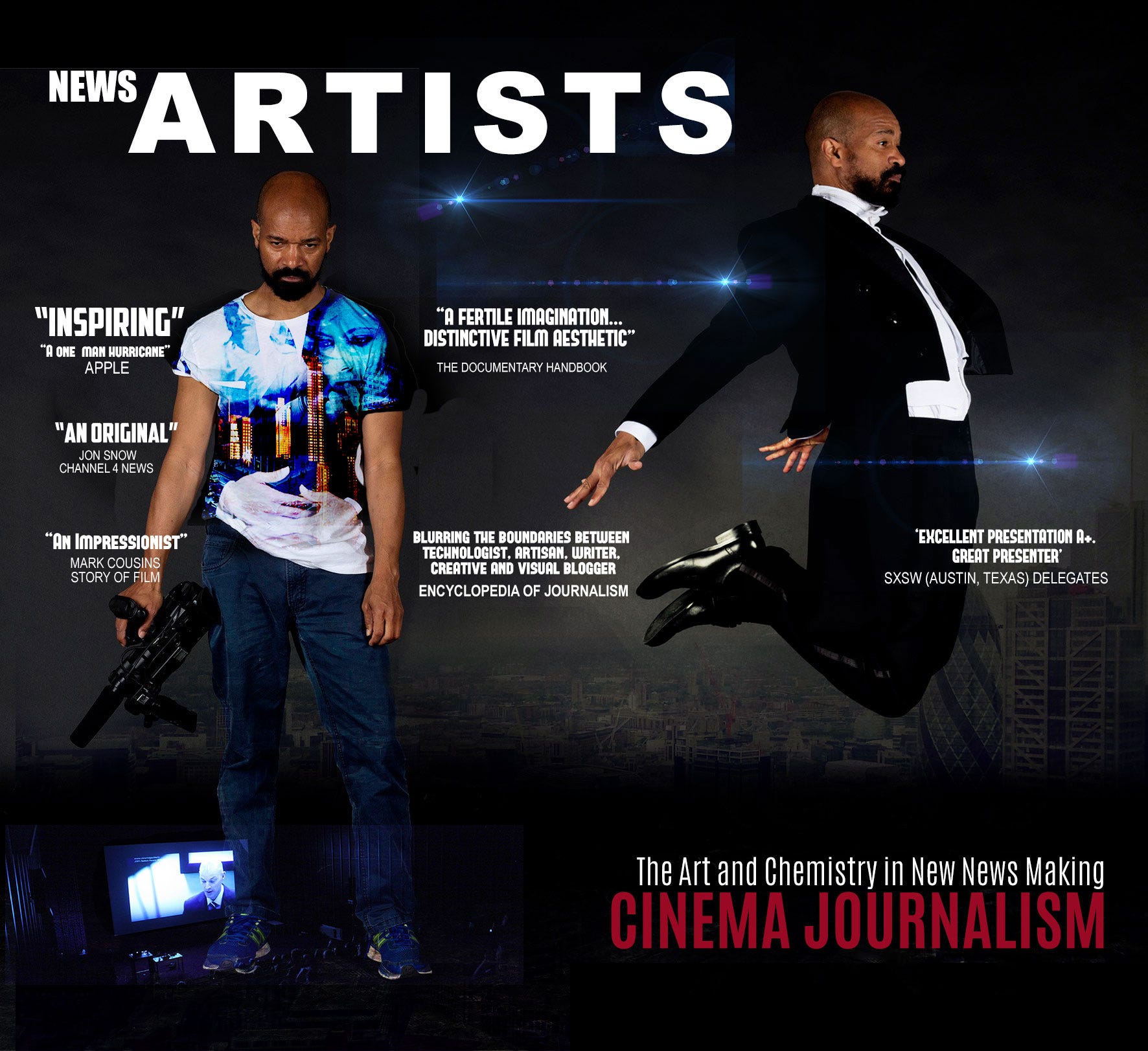

I’m a university lecturer, a job I love and for several years have swapped ideas and methods with Masters students. In between lectures, I’ve pursued my interests that blend conceptual storytelling in cinema journalism (my practice) with Tech and Diversity creating events like the Leader’s List — an exhibition film of the UK’s leading TV producers of colour.

The art of collapsing cinema and journalism which builds on Cinema Verite is still unfolding and I get goose bumps every time I think of the kind interactions and interviews with the doyens of Cinema Verite and Cinema like Robert Drew, and Mark Cousins who helped me get here.

About a year and a half ago, a senior personnel from the British Library contacted me. Would I be interested in becoming an advisory board member for their exhibition of three hundred years of news — planned to open in 2022 because of the pandemic. Sure. That’s some canvas I thought. Imagine a film that would cover that period? In this case, a book accompanying the event is to be published and I feel indebted to the British Library that I could contribute a piece on language and BLM.

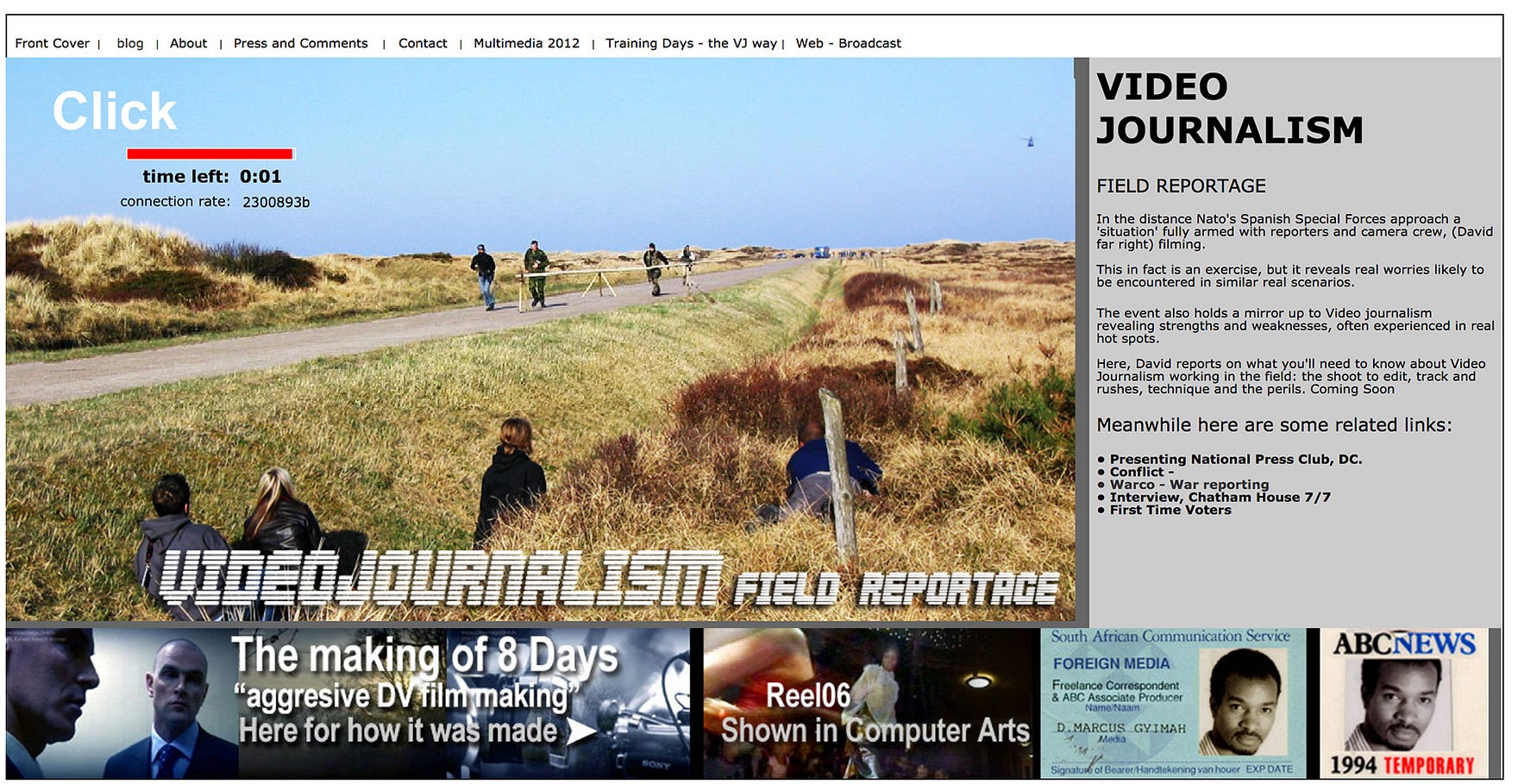

The thing with storytelling at an institutional level is it’s like a virus in that it never leaves you. Since I formally left the broadcast industry working on programmes like Channel 4 News, I like anyone in the do-it-yourself YouTube Gen., continue to tell stories on YouTube and my own platforms.

But there’s something enticing, alluring and intoxicating about presenting to a live audience, or on a big stage. The last two big-staged films were made whilst I was an artist in residence at the Southbank in 2011.

Re: Sounding Motion saw exceptionally gifted young people with music or dance skills being provided with exemplar levels of training and putting on a show at the South Bank Centre. The other was Obama’s 100 Days with the classical composer and conductor Shirley Thompson OBE.

These kinds of works have the habit of pushing beyond self-imposed boundaries with one eye focused on the intended audience that will judge your work. There’s the propagation of critical ideas which consciously marry thoughts accumulated over one’s journey. There’s also equally, in seeking commissions (broadcast or public), the oft intimidating round of interviews to generate interest accompanied by the “Thanks, Sorry !”

When I started in the early 90s I remember how painful they were. I would find my own soul-sating stories by relocating to South Africa where I could roll together all my interests. Today the impact of “Thanks Sorry” (TS) is no less but the years teach you to understand everyone (nearly) gets TS’s. Frankly if creating art was that easy what would that mean? The pain and struggle of creation is a part of the gain, isn’t it?

Afriend offered to help with the selection in my garage. Firstly what if we presented it to the yearly contest that is FIAT/ IFA — a global body that seeks to preserve important archive. Against eight global finalists, the pitch about the archive’s contents was made online and three months later we were informed we’d won.

Jose as archivist producer drove the conversation to digitise the batch; some 800 hours plus of tapes, audio and video, small by comparison of archive found tapes, but no less valuable.

And that’s the point. These 90s tapes are personal but also mark a socially detailed aspect of that time. There is the interview with Nigerian Superstar Fella Kuti that I turned into a story for the Journal Representology — a joint venture between my uni (Cardiff) and the Sir Lenny Henry Centre at Birmingham City University.

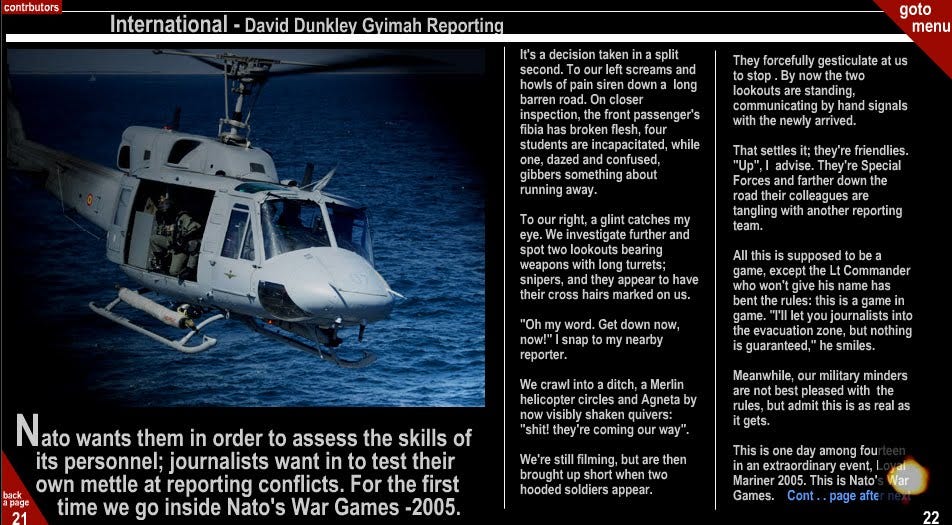

There’s the interview with the director of the touring show This Old Minstrel Magic derived from the Black and White Minstrel Show (Black face) who tries to convince us no harm is being done in reviving a show “everyone loves”, he says. There’s the film collectives of the 90s and Melvin Van Peeble’s telling me about the revival in black filmmaking and his own film Sweet Bad Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss. And this, in the depth of South Africa’s belly of turmoil I ride the night with peace activists in Katlehong, designated murder capital of the world.

The archive selection include a ‘documentary lit’ interview with one Reverend Pearson whom in the 1940s would befriend the King of the Ashantis. Their friendship would result in a school attended by boys who would become presidents and Ghana’s political class. The short promo I cut a decade plus ago was narrated by Channel 4’s Jon Snow.

Listening back to them has been a journey down memories, which is all well and good for me, but what interest might they have beyond my garage doors? I’ve been struck by many of the issues which are current today and have their voice in the stories from the 90s. That shouldn’t be surprising. Frankly you could go back further to the 60s and further back still if the archive existed to help viewers and listeners understand current affairs.

Back then there seemed little appetite to log or archive ‘Black’ stories. Some of the stories were broadcast whilst presenting Black London on the BBC. Another presenter and I were paid the princely some of £30 pounds for presenting the weekly programme.

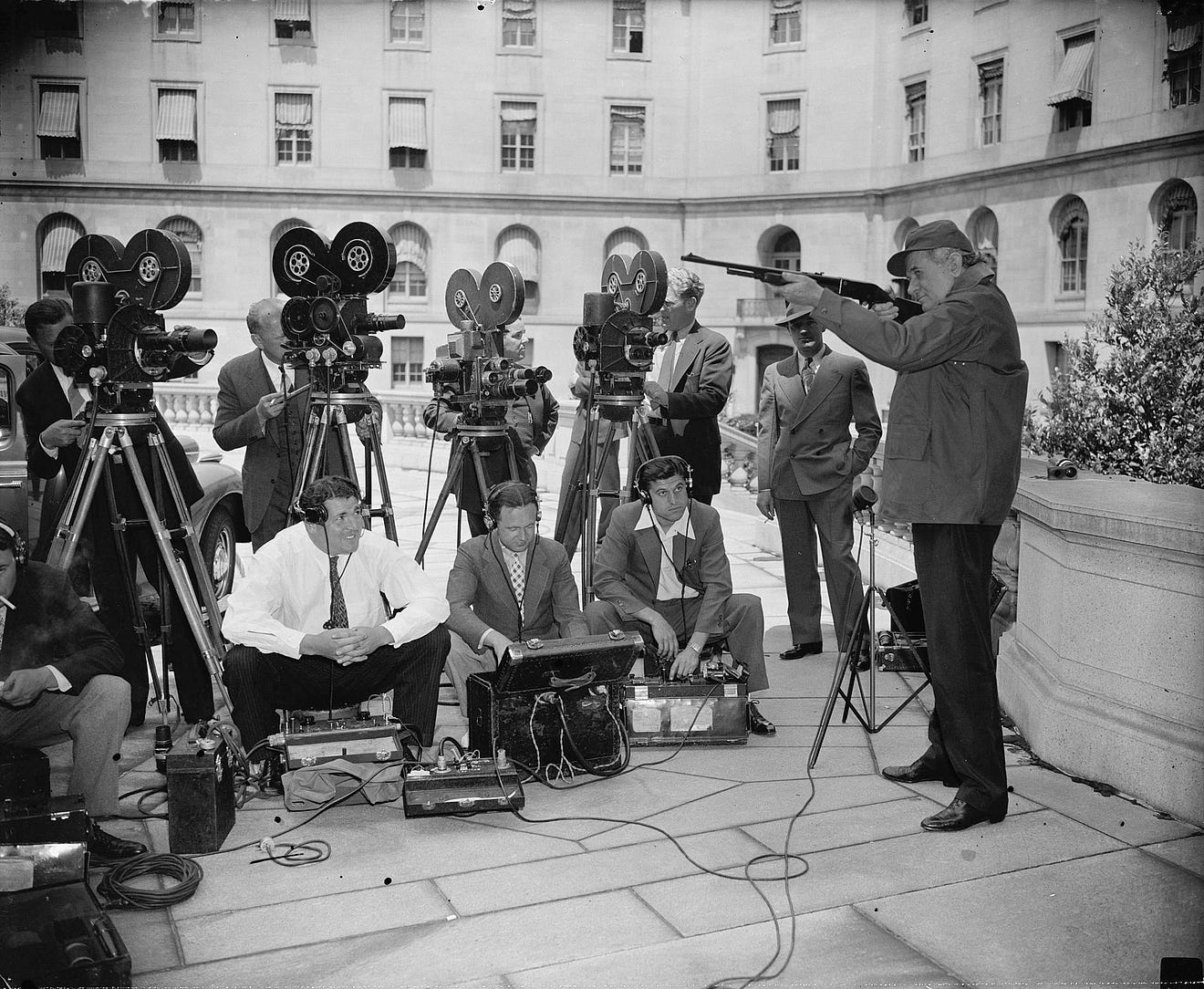

And this. What happens when two of Africa’s respected broadcasters: Ghana and South Africa come together to explore each other? The programme, a six parter, was the United States of Africa. It wasn’t just unique in how the Ghanaians reported on South Africa (newly liberated from Apartheid) but that in 1996 they were using videojournalists and digital cameras way before the BBC or CNN was.

The question is what to do next? A sound installation? A programme that feeds off the archive? A monologue interspersed with archive that gives an account of London circa 1990. One thing I’m certain of is the value it will have for my Masters students; I’m inclined to think the value may extend beyond them. Who knows? If you’re a commissioner/publisher and this interest you, please drop me a line @viewmagazine or David@viewmagazine.tv

About Me:

I’m a writer, academic, storyteller and creative technologist with thirty years experience working across broadcasting, advertising, and academia. I have recently completed being Chair of the Organising Committee for Cardiff University’s global Future of Journalism event ( keynote included Gary Younge) and advising for the British Library, and am due to relaunch the Leaders’ List. More on me here.