In the 1970s the unthinkable happened. A thriving industry by which the public was informed about the latest news and current affairs was largely proclaimed dead. New media technology, swiftness and style from a relatively new contender, television, made Newsreels unattractive to audiences.

Some years earlier no right thinking Newsreel executive would ever have imagined their days were numbered, even links with a fledgling BBC getting into the TV news market. They (BBC) need us, would have been any riposte to impending doom.

Since 1910 with the first newsreel by the French Pathe called Animated Gazette, and the gaining in popularity in the 1920s, with films from outfits such as British Movietone News, the public were sated by Newsreels.

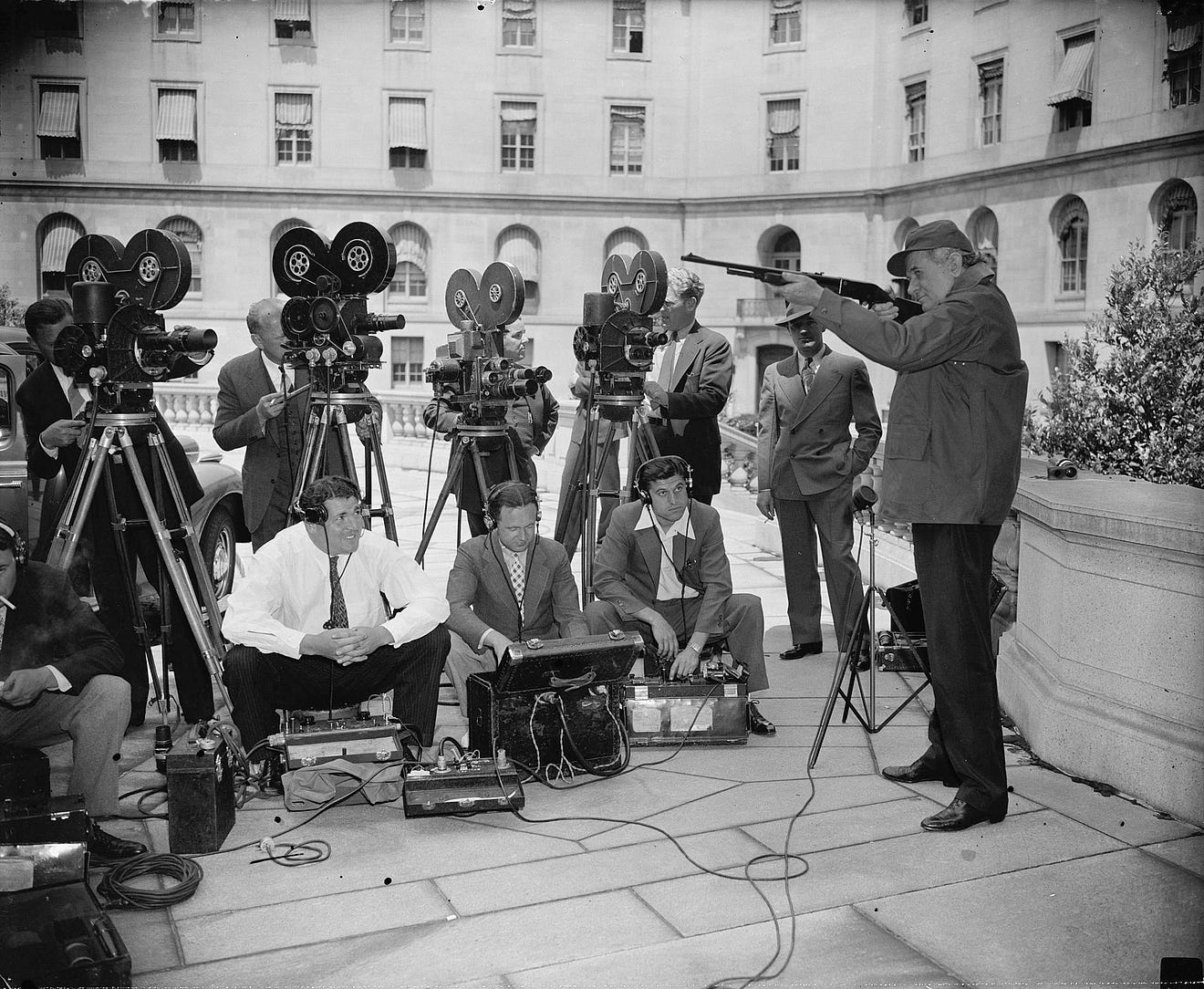

Features could vary in tone, such as serious news and war coverage in which cameramen used revolutionary small hand cameras, compared to the clunky (Mickey Mouse ears) ones in use in this photo.

The arrival of Black Britons on Windrush was covered by Newsreels, explained here in an excellent piece by Dr Luke McKernan from the British Library.

Then there was the absurd and fashionable and an indifference to news with , jaunty music and jocular mocking narrations, that would earn Newsreels scorn from scholars.

Television News hadn’t been invented in the 1940s, much less refined in the 60s from what is its legacy today. Public arenas designated as cinemas would take to showing five minute features of news from around the world before the main feature. It would be the equivalent of watching, what would now be, a BBC news bulletin before Bond’s Skywalker at a multiplex.

Here’s where the record on history scratches to a stop, and the real relevance of this piece begins, because the shunned newsreel executives from yesteryear may be in for the last laugh. History, does at least have a sense of humour.

No right thinking television news exec would contemplate TV News dying. It’s a multi billion industry, but the writing is writ large on the wall of AI, consumer choice, and new styles.

Just as the threat to Newsreels were technology, style of production, and immediacy, the threat to TV News is the same.

And just as new custodians took over from the old guard, so here too the new contenders will oust an antiquated form of production. This 30 second clip here from a previous senior BBCs News executive sums it up.

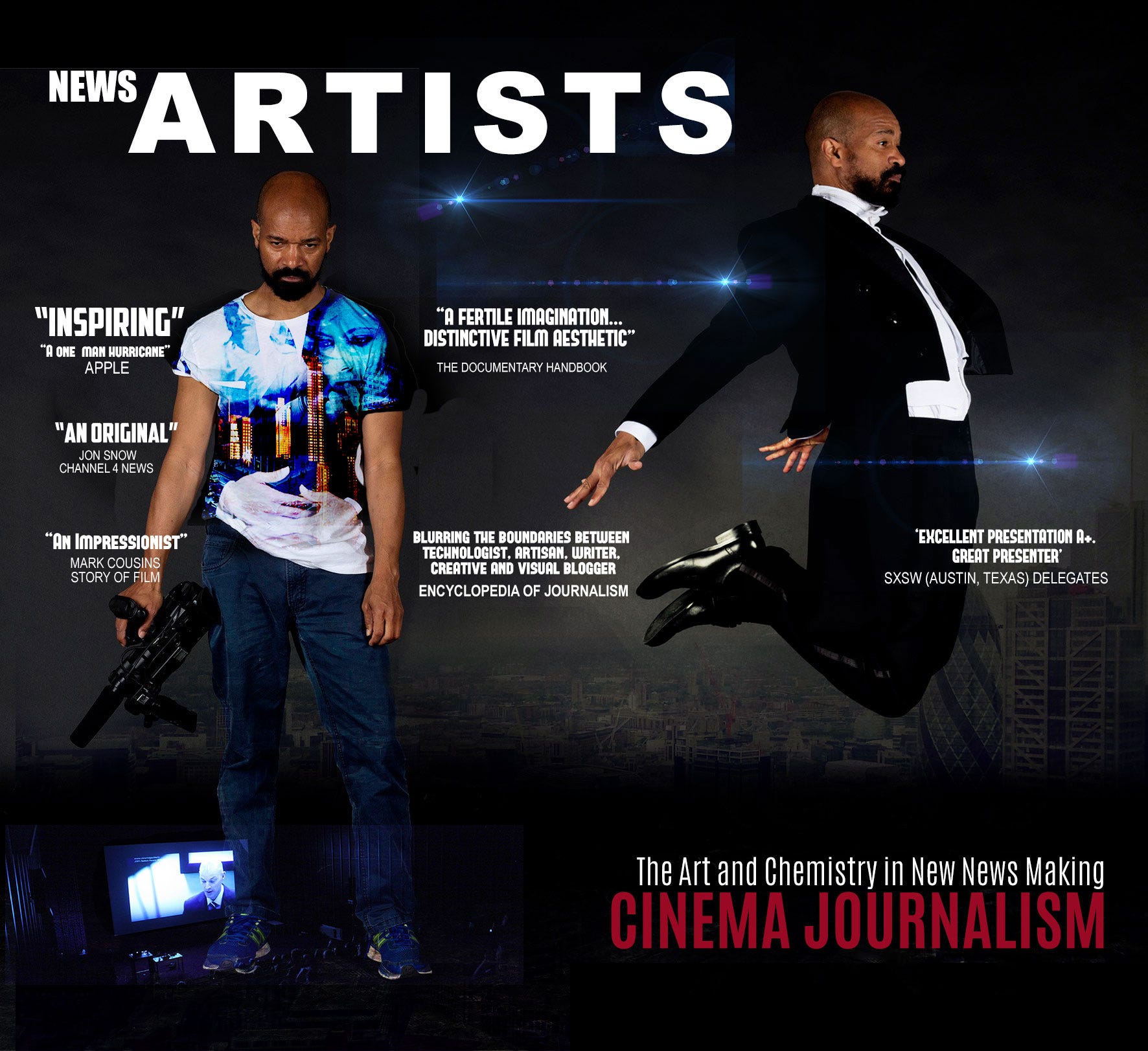

I started tracking this phenomena back in the 1990s, when I was part of a UK-wide media social experiment. This piece’s cover photo (thank you David Freeman) signifies the duality in analyses.

Firstly, the experience as a journalist who makes news films and has been doing so since 1994, when as a videojournalist it was unheard off. I’ve since trained thousands of journalist across the world. And before then reporting from Apartheid South Africa for the BBC World Service.

To the executive and academic side of explaining future trends in storytelling, such as here as a keynote speaker to one of the city of London’s dynamic entrepreneurs, The Guild of Entrepreneurs, and News Xchange.

This week I had the opportunity to speak to staff at a TV station in Denmark about the future. The threat to television exists, from amongst others, technology in AI, public boredom with the status quo, but also new platforms in streaming services. News, but not as you know it, in the same way Newsreels were caught napping is about to have a sense of de ja vu.

“A style of delivery that hasn’t changed… cannot be the answer” in the above clip, says Pat Loughrey, so what is?

Ironically the very thing ‘cinema’ discarded in Newsreels is resurfacing with lessons learned. Cinema back in the 1930s meant different things, a venue and style of filmmaking and not necessarily fictional.

In the 60s one pioneer, Robert Drew with his friends such as Albert Maysles (photographed here at the Sheffield Documentary festival) was transparent about it, giving his way of doing news, a label, “Direct Cinema”.

It survived, albeit in limited form. News executive would be damned if they were going to let a style of filmmaking overturn a business and class model which was gaining ground.

From here to the present lessons have been learned. What will prompt change is happening right now in the shape of new streaming services. Not by taking a style and transposing it on this new form as news executives first did with the Internet. They simply lifted the newspaper onto the web, but by acquiring fresh thinking promulgated by audiences.

At most a decade is the cut off point. It’s easy to sneer. This cutting from 1963 spoke of Mobile phones in the future; something I repeated with a team speaking to the BBC in 2004, when mobiles as they exist then hadn’t surfaced.

The question you might ask yourself, as we have done in our Future Lab, is in the face of change and mergers, such as AT&T’s intended fusion with Disney, what would happen if Netflix or HBO did News?

The future of this revolution, much like the industrial one the shaped the multi-billion pound art industry will involve audiences seeking to come into more contact with new news artists. Expressions will be based on what the artists see rather than what they know. And it will fuel a yearning for new content and innovation from audiences, proven by Netflix’s growth over the last 15 years. People easily forget the past in a hurry even when the provider is one of the News behemoths. We know this by the history of Newsreels.

Dr David Dunkley Gyimah has been a journalist for more than thirty years and a technologist with a degree in Chemistry and Maths. He was an artist-in- residence at the Southbank Centre under its artistic director Jude Kelly CBE. He is based at the University of Cardiff. More on his background here