It’s 7.40 pm and one of the most powerful editors in the UK is standing over me. He’s looking at me squarely and says something that’s ringing in my ears in slow motion as he walks back to his office.

“I’m going to be fired. I’m going to be fired”, I’m thinking.

“You get him, right! You get him”, he says.

How?

On the 6th of BBC TV Centre, Shepherds Bush, is the offices of Newsnight. When you enter it’s humming rhythmically to the sounds of programme making. Chaos, events about the world are being converted efficiently into meaningful stories. I’m in the corner on the left.

A little dorky, wet about the ears, five months out of journalism post grad, I’m a researcher. I’ve been on the programme a couple of months, but now the adrenalin accompanying a big story breaking is causing mild panic and a sense of “I’m out of my bloody depth!”

For the last eight hours I’ve been periodically ringing around pulling potential interviewees into a story package and an item on the programme. My desk is strewn with papers and a drawn spider’s web — a mind map.

But there’s one person whom I have called at least four times, and who’s been extremely accommodating as a quasi deep throat — giving me other contacts — but won’t come on the programme himself.

It’s the biggest story going.

On 29 November 1991, after an eleven-week trial at the Leicester Crown Court, Frank Beck, a presumed respected childcare worker, in charge of several children’s homes in Leicester, is sentenced.

He receives one of the most severest life sentences in the UK for sexual as well as physically assaulting more than one hundred children in his care. Beck gets five life-terms and an added twenty-four years for seventeen charges of abuse, including rape.

Researcher’s syndrome

“You get him” I murmur. Editor Tim Gardam is referring to a high ranking official speaking on behalf of the government who will explain how this could have happened.

I place another call except this time my words and tone will change.

“Uh-er, uh-er’ he acknowledges on the phone and then I go serene-slightly sullen- mode, “I’m really sorry but if you don’t come I don’t think I’m going to last another day here”. He listens and says let me see what I can do. I have to speak to a number of people.

This evening, Newsnight is presented by Jeremy Paxman and my presumed-in my-head-friend-at-a-distance pundit makes it onto the programme. Paxman grills him. Paxman does what he does.

I’m certain what I said didn’t change whether he’d come on or not, after all BBC Newsnight is the draw and he, well, is an official. I might cry rivers on the phone and it wouldn’t change a jot, but throughout our earlier conversations they’d been engaging and stimulating. I’d read up enough to have conversations with my pundit demonstrating my knowledge and showed gratitude for his suggestions.

A friend suggested when you’re speaking on the phone, stand up. It allows you to gesticulate, be more expressive and use your diaphragm more. He was one of the best telesales people I knew. His openings followed a rehearsed script.

I sensed a rapport, illusionary or otherwise, with the official. I actually felt he wanted to help this voice at the end of the phone. “Ah hello!” I remember greeting him as I picked him up downstairs in reception. After the show, in the green room, I thanked him profusely. I lived to see another day on one of the UK’s most terrifying, but enjoyable programmes.

Yesterday, I spoke with my Masters students readying themselves for the push to their final project. It appears daunting, more so in times of Covid-19s lockdown.

But lessons I learned from those years back can help today. There was no Internet then to aid research. It was performed via cuttings - looking through realms of newspapers, spotting names and making a spider’s web — a spatial grid of speakers and their relationships.

What did I learn?

№1. Persistence and courteousness. I never went nuclear again. I was embarrassed. But I learned it wasn’t personal. I’d rang up several interviewees that day; the one that seemed like nay impossible, in reality, some of his suggested speakers would have done. But these too were the times when officials couldn’t empty chair an interview because of hubris, as the government does with wanton abandonment today.

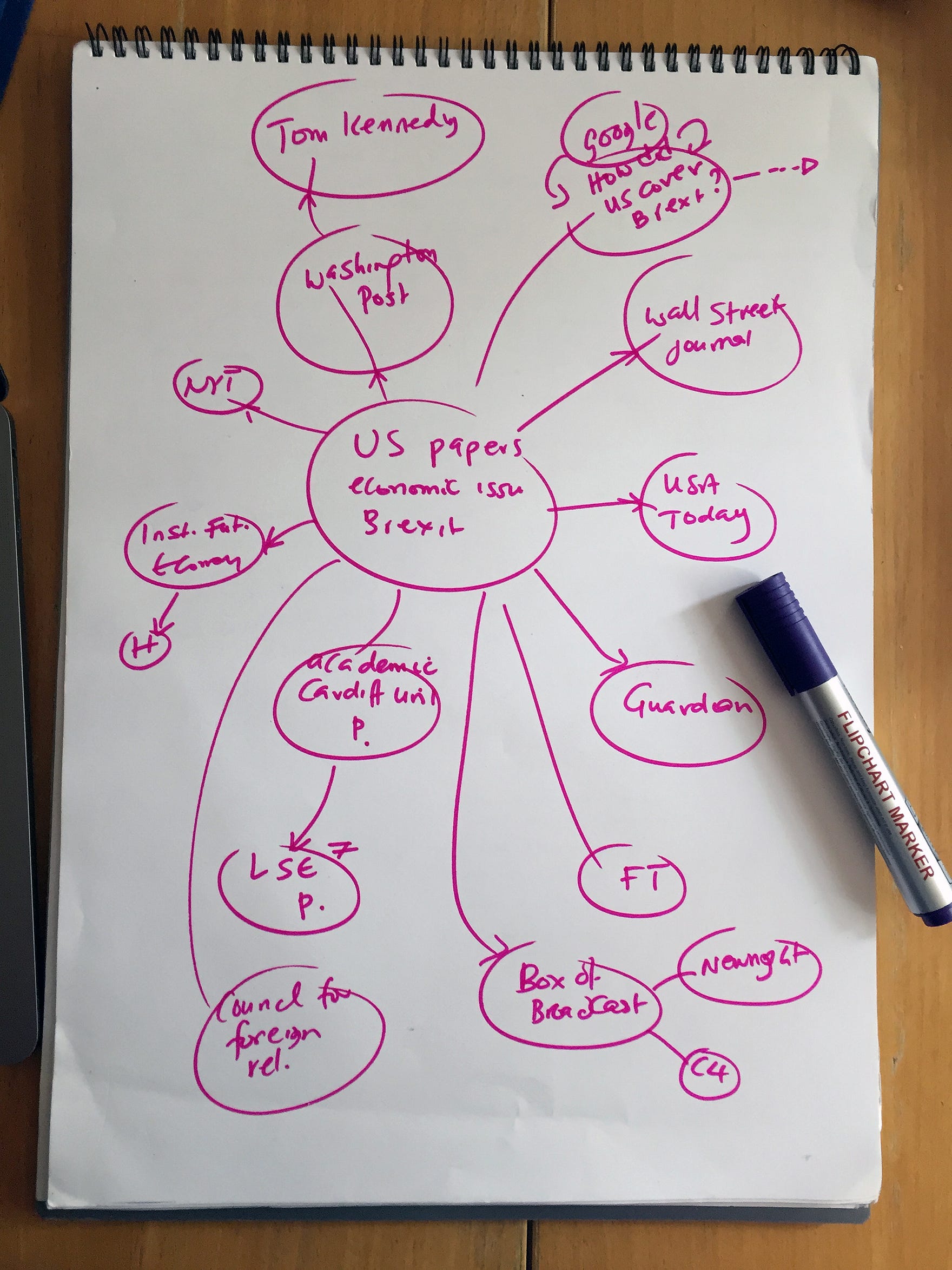

№2 If you watch “Homeland”, “Law and Order- Special Victims Unit” or any number of crime flicks, you’ll see their spiders web in play. A central character is connected through a narrative to others in the syndicate. Here’s Mojos top ten detective mind maps

It works equally well too for mapping interviews. We think spatially (right side brain) and its easier for others to see your work and make connections in one fell swoop. There! And the lesson in building a spider’s web of contacts is that it’s shareable and others can add to it.

№3. After I would speak with an interviewee, I would always finish by kindly requesting a recommendation. “Who might I speak to as a matter of interest to get deeper into this story?” It didn’t control my direction, but was a guide track.

Current Affairs Workflow

In our zoom meeting yesterday I illustrated the spider’s web in action, taking one of our MA student’s project. Rachel is looking at how US papers reported Brexit.

Step 1

Here’s my doodle (Fig I) as she shared details. The links are either potential speakers or contacts she’s yet to make. It helped me make some suggestions on top of hers. Consider this: does the map make it easy to see Rachel’s initial research and importantly can you, reading this, help by suggesting other links?

At Newsnight, I was struck by how producers could assemble programmes so swiftly and easily.

Months later though I would have the opportunity to put into practice what I observed when I joined one of the BBC’s most dynamic, fun and feisty programmes, Reportage. Before there was Vice.com, there was Reportage.

The programme brought a new level to research and production, a synthesis of styles from people who’d worked at the creme of news and current affairs and would go on to make huge contributions in television. These included Tony Moss, Jane Knowles, Hardeep Singh Kohli, and Caz Stuart to name a few.

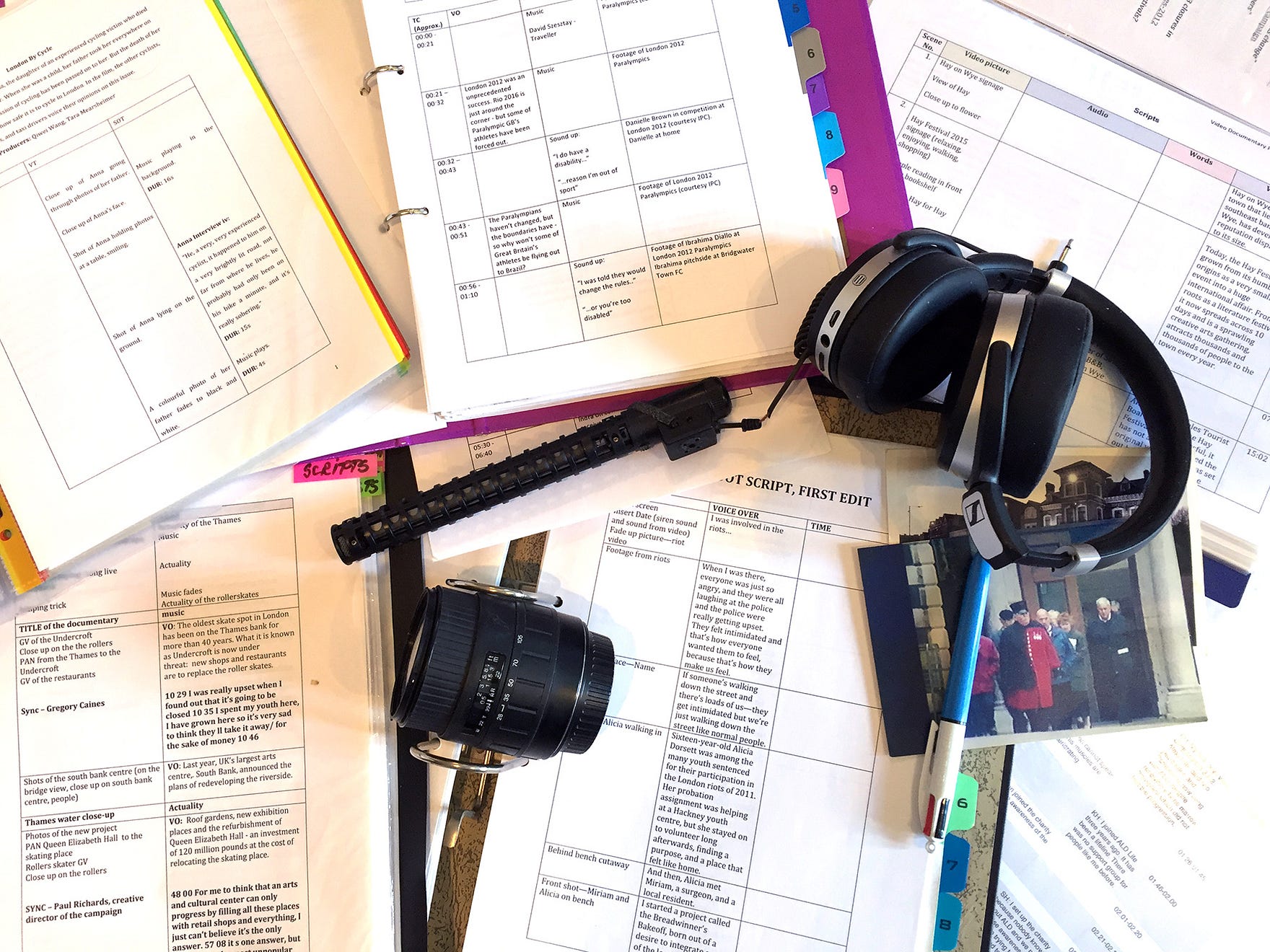

Reportage’s adopted system is one that many programmes, TV docs and current affairs, use. It allowed teams to turn around a 10 minute story in two weeks. That is from the idea, research, previsualisationm,shooting the storry, multiple edits and then going to air.

Later in my career as a producer at Channel 4 News, and creating 7 min plus feature stories and as the reporter/ research BBC Radio 4 Docs, I used the same approach.

Step 2

Let’s imagine I have interviewed Tom Kennedy (from Rachel’s spider’s web. Fig I) who’s a good friend of mine. Tom used to be the Managing Editor for Multimedia at the Washington Post and Newsweek Interactive.

In my interview with Tom I record our exchange, asking his permission before hand and then transcribe the interview. He says several things I find useful.They are illustrated in pink lines (Fig V). But when I listen back to his interview whilst attaching time codes (logging), I’m drawn to quotes that stand out, which I’ve enclosed with blue lines (see fig V below). At Reportage, we’d go, “Whoah that’s a great SOT”. SOT is the same as saying quote. I would share my transcript/ and/ or my quotes with the producer. My producer would be my second eyes, offering a critique (not a criticism).

Whilst I have a skeletal framework where I’d like to take my feature, I’m being influenced by the strength of the strong quotes I’m reading. This is the equivalent of a “close reading” in academia.

Step 3

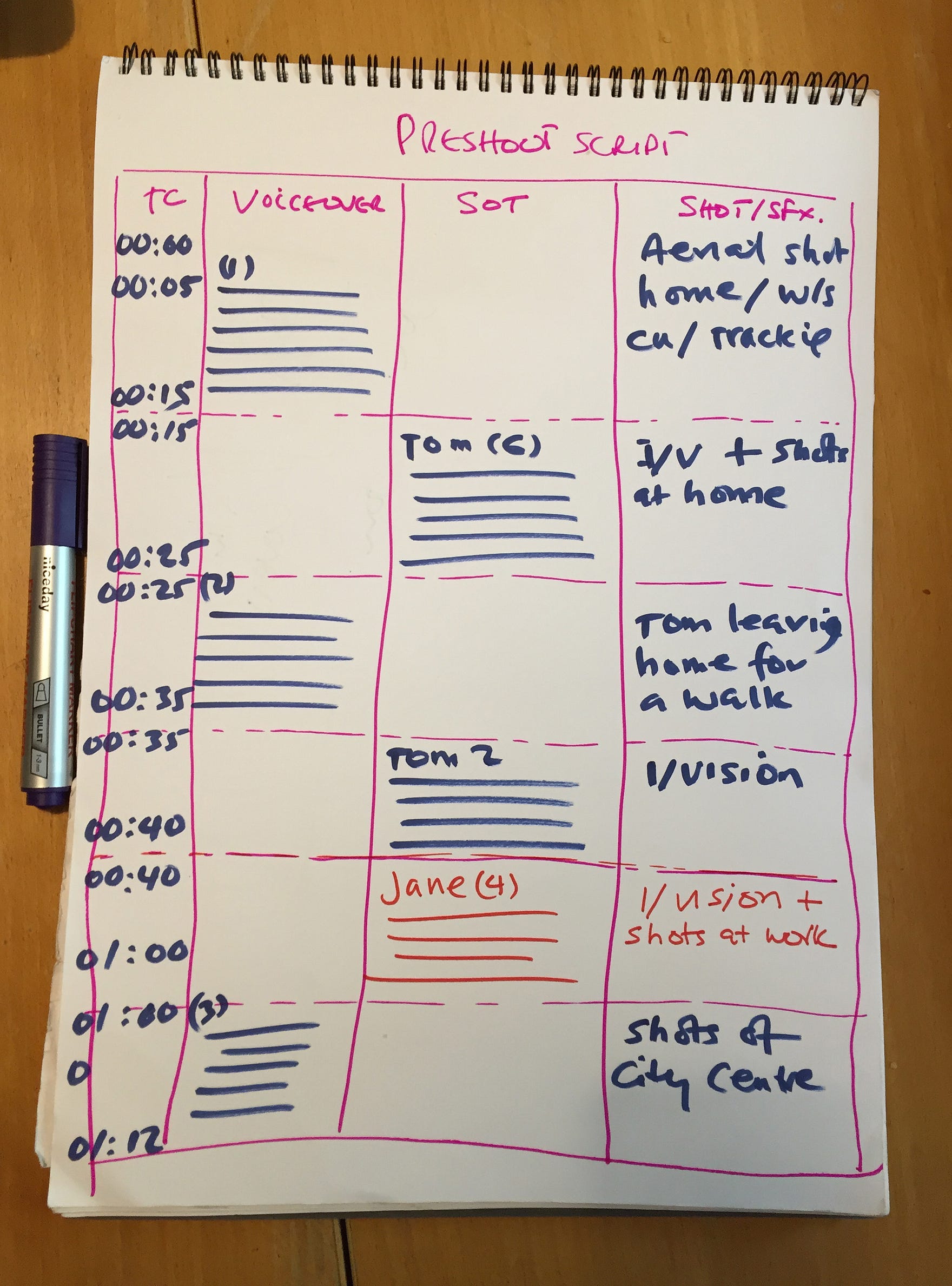

My next phase is to think of a flow. I have an idea of what each one says. Can I devise a pattern of how to structure them together? Essentially this focuses on continuity editing. This (VII, below) could be an example (in principle I have just made this up but you get the idea).

I start with Tom and then think of pulling in other speakers (using the same script highlight method). Jane( from Atlantico) is followed by P. from LSE and so on. You’re constructing your story world — a way you view the story. In film making outside of Television, often referenced as documentaries, there are an endless array of styles e.g. essay, which you’ll likely be familiar with.

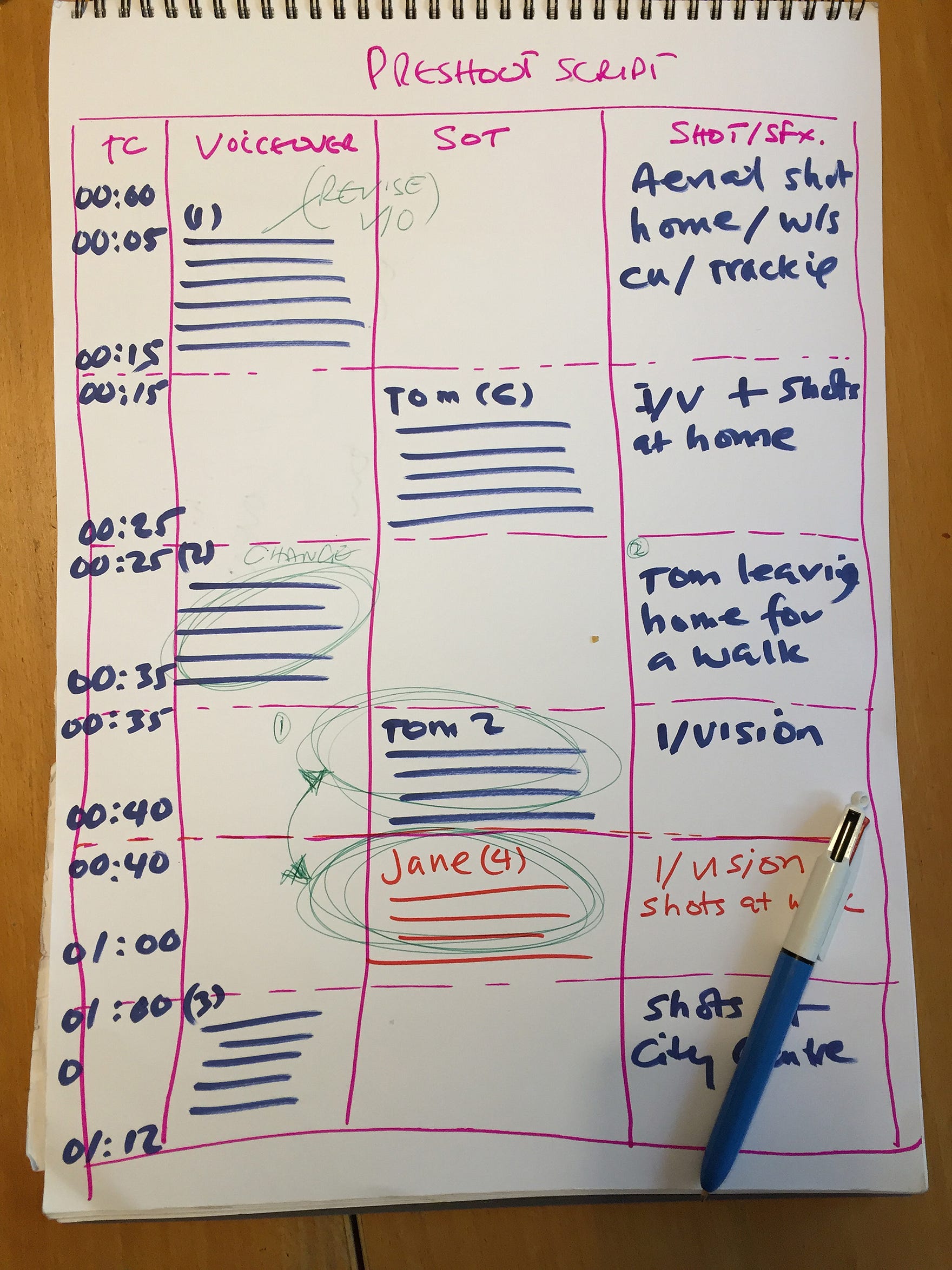

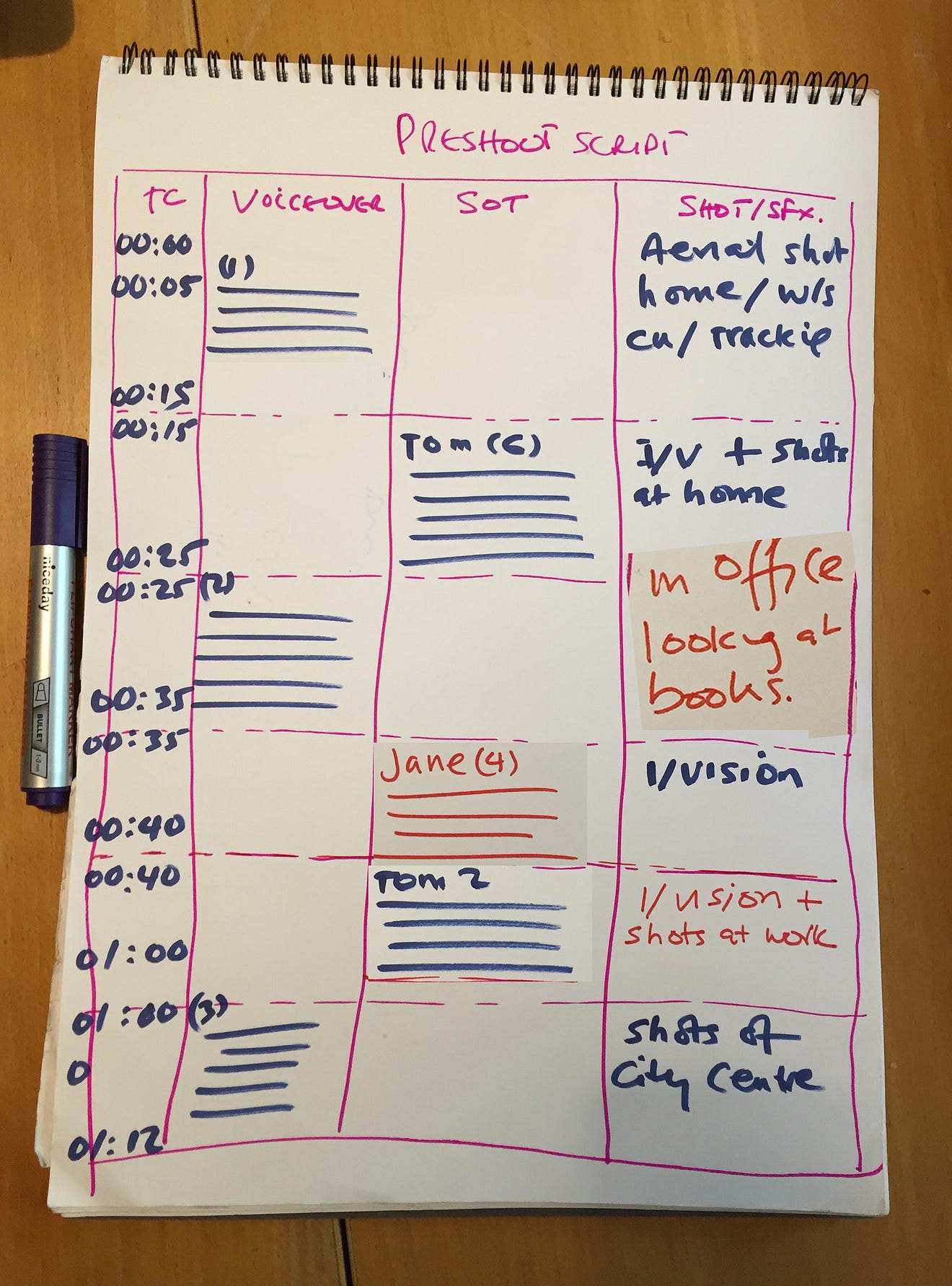

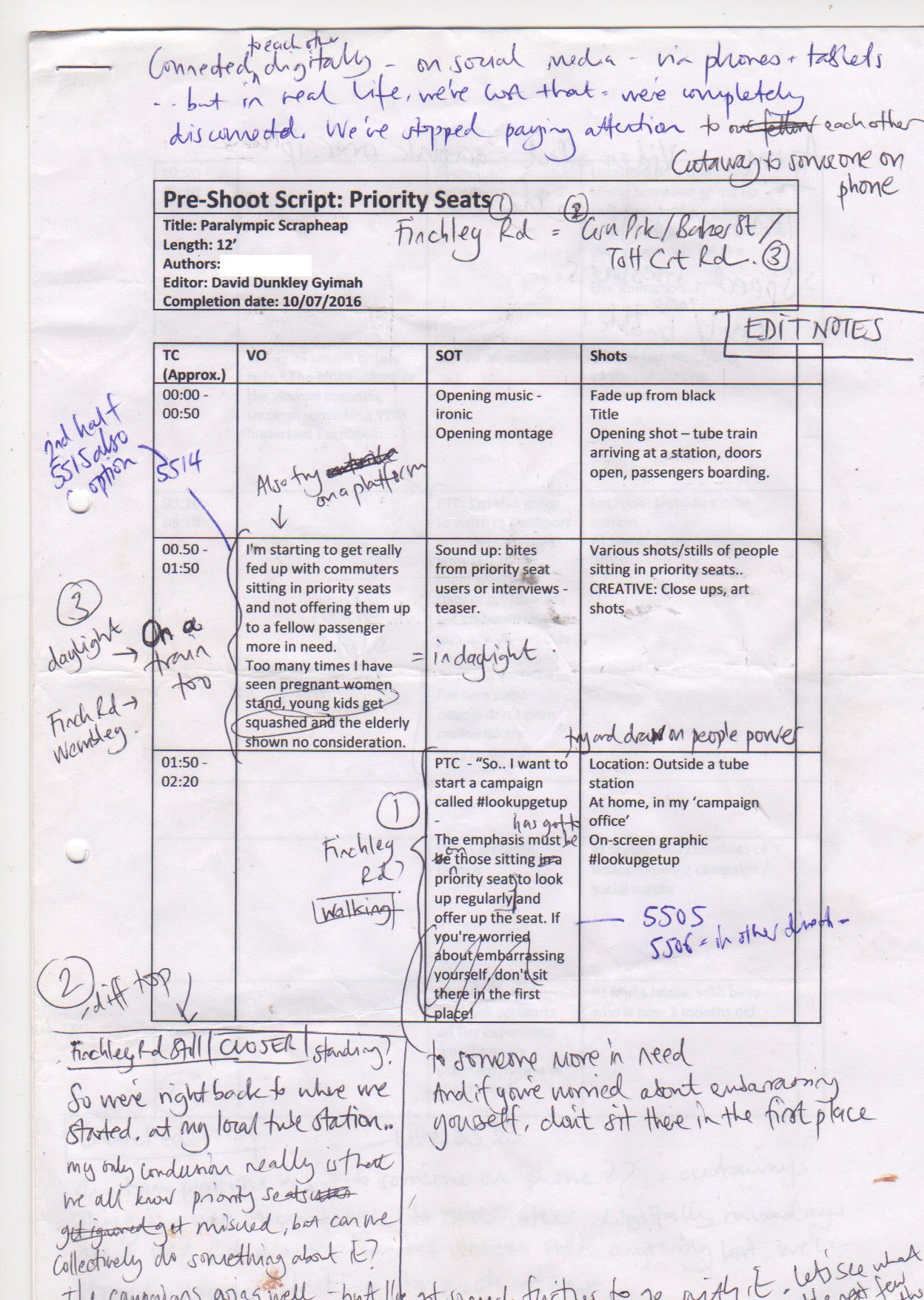

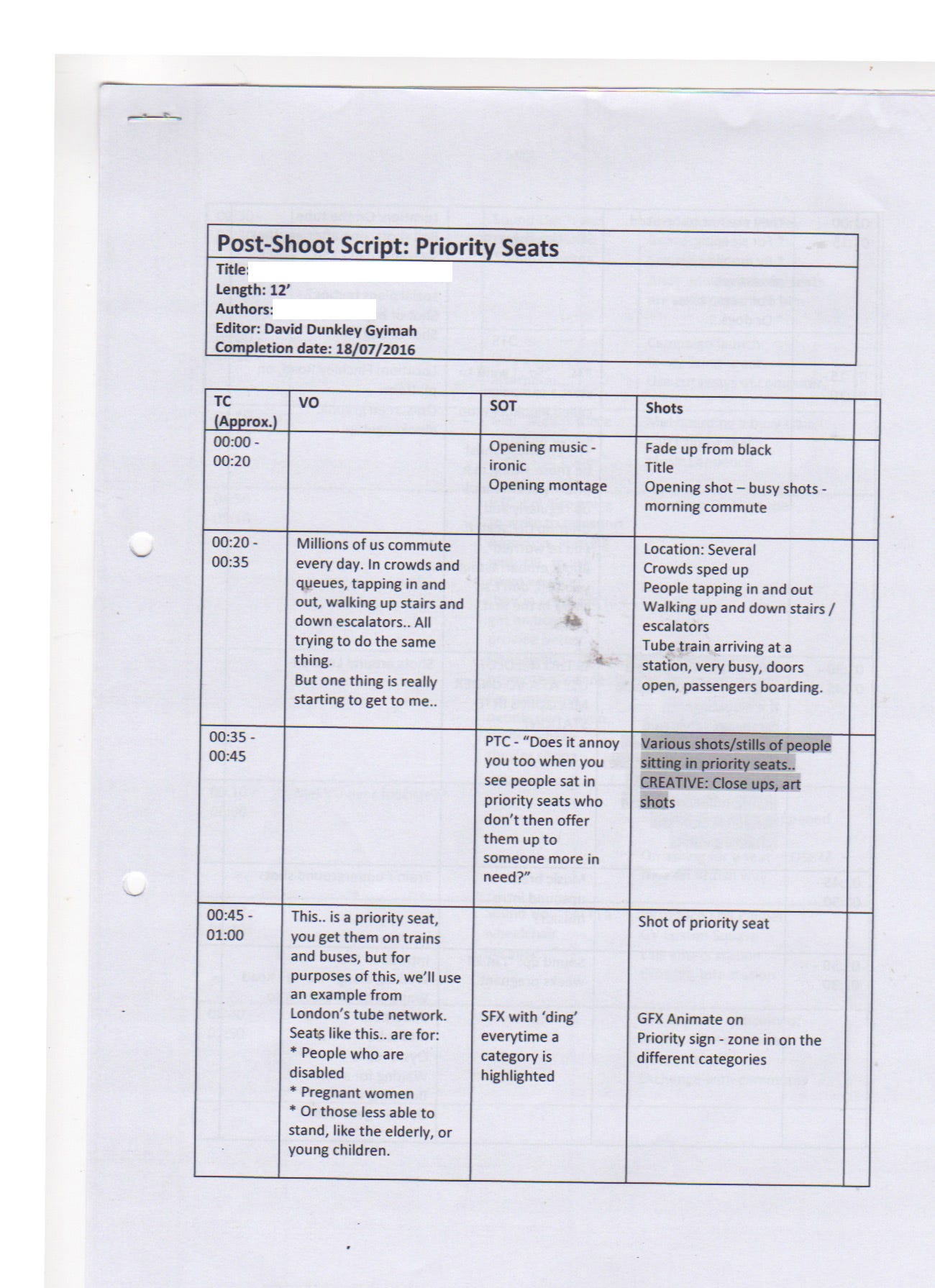

Using the above structure I attempt a pre-shoot script. It’s a script that visualises the film from interviews, location, and related research. Here are examples of pre-scripts of previous students spanning fifteen years.

If you’re creating a documentary/ feature where there’s no need to share your work, then frankly you could go into the field with a loose structure in mind and film to you heart’s content. More often than not, it’s in the edit where the film takes shape.

The architects of Cinéma vérité or correctly referred to as Direct Cinema from the 60s, such as Robert Drew, used this method. Here’s my interview with him.They would film realms and then construct a narrative in the edit. Award winning doc maker and videojournalist Raul uses a loose structure (Fig V) and pre-interviews in the field before deciding what needs shooting. His award winning international is likened to a watching a movie. This is his latest film, The Virus.

Step 4

If you have time constraints and are working in a team, then open transparent planning will help you enormously. This is what we do next.

From the structure and the interviews (see examples, fig VIII and XII) attempt to pull quotes into a story structure. We’ll use Tom Kennedy as an example again. Dividing the page into four grids; the columns are interchangeable, I’ll construct a narrative around Tom’s quotes and several others, such as Jane (Atlantic) who I also get to speak to.

Time codes on your left, followed by Voice Over, SOTs — which is the same as clip — and then shots.

My voice over (represented by blue lines in this case) is scripted and works into the Tom’s (6) quote, lifted from Fig V. I cover that Voice Over with aerial shots.

Tom is interviewed in vision i.e. we see him and then there are overlay shots of him at home. You’ll notice the time code increasing on the left column, each time a voice over or SOT is added.

Voice Over no.2 covers Tom leaving home for a walk. Now the point is we haven’t shot him yet, but that’s what we envisage. That’s the pre-visualisation.

Tom’s (2) SOT from his interview from Fig V is buttressed against an interview we did with Jane ( Atlantico) and that’s followed by another Voice Over covering city shots as we move the story on.

Step 5

After consulting with your editor or supervisor, you might decide to swap Jane (4) and Tom (2) around for impact. If that happens the Voice Over into Tom 2 and the shots of Tom leaving home for a walk would also have to change. The image above shows this.

We might also see some changes to Voice over 1. These changes aren’t necessary, but more often than not will occur in a pre-script because of new ideas and reflection. In changing SOTs around in the two images above there’s one thing I’ve not changed. Can you spot it?

You can see an example of a pre-shoot script in practice here (Fig XII) from a previous student who took a career break from working at Sky News. She made changes, shot her piece, and made further changes. We met three times in between her pre-shoot and her final edit.

This is Natalie going though script surgery. She’s now a video journalist at the BBC, and Tamer who graduated to become BBC Correspondent, before becoming a reporter and doc maker for Al Jazeera. I made a film of Natalie and colleagues finishing their projects here #Student You.

That pre-shoot provides a template to film, and replicate. Of course when filming new ideas may arise; somebody might drop out, something entirely new may emerge, but the point is if you’ve done enough preparation so the integrity of your film will hold. You’ll cut down the amount of work done in the edit. That’s how on Reportage, and other programmes like Panorama, a report can be turned around in less than a week.

Side by side, you can see the progression. With revisions to the pre-shoot script, you’re ready to start filming.

On the shoot, there will be changes that will lead to changes to the script, which through the production process becomes the edit script and then the final transcript. So far you’ve prepped the Interviews and the story, and parts of the location. In the next post, I’ll talk about prepping the camera gear to shoot cinematically.

NB. Marcus Ryder, (@marcusryder) a former Senior executive at the BBC who led Panorama leaves this important tweet, ff by @writersroompublishin.

Larry Anderson, a Transformational Change Lead at Nike left this message

Dr David Dunkley Gyimah, presenting at Apple. His work, as a video journalist is featured in The Documentary Handbook, where he describes his craft as follows:

If you could combine the art of motion graphics and photography, the mis-en-scene and arcing of the cinema, the language of television, the skill of radio with users’ behaviour online, I believe we would be closer to understanding the power of video journalism.(2005)