They’re coming for you. Not the AI per se, but the CEOs driving AI. And to ensure you can still make a living you need to find your super power. That much I’ve told several writers recently, some from the BBC.

They’re coming for you. Not the AI per se, but the CEOs driving AI. And to ensure you can still make a living you need to find your super power. That much I’ve told several writers recently, some from the BBC.The CEOs won’t save your job. Their vision is to push the boundaries of tech knowledge, make considerable wealth, achieve Maslow’s highest order in its hierarchy of needs, and maximise shareholder profits. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong in this if you believe in the unfettered machinations of the market. But all is not well, was it ever?

The consequences of so many people losing their jobs, first it was unskilled labour, now the skilled and creatives are realising the heat, would border on incivility in society and a political class literally operating behind defences minimising contact with their electoral shareholders.

So what’s the solution? There is a model that could work, that could stave off complete disruption of work and leisure. It’s been proved to work and it won’t stem from CEOs stopping any AI development until policies are framed.

It’ll require human-ai co-operation and for humans it’ll mean finding your super power. And where might you acquire it from?

Onthe 11th May 1997 in New York City the world’s most formidable chess player Gary Kasparov would do something that shocked the world. He lost a chess tournament to a computer, IBM’s Deep Mind.

The world of AI had taken a major prize. A nascent technology in terms of its prowess today in neural networks and reinforcement learning, it provided an insight into the future.

That future was a year later when in June 1998 in León, Spain, Kasparov fought back. His solution, he explained would make chess players better, make the game more accessible to a wider audience, and would ameliorate technologists. It was a move that de facto set up a blue print for human-ai interaction.

Advanced chess, his design, brought humans and computing power together. It was predicated on his belief that some part of what humans did in chess was better served by computers, tactics. Kasparov could detect gains from individual moves — a feat bestowed on grandmaster chess players seeing the board in several patterned plays. But computers had an Achilles; they were poor at overall strategy — the overall sum of the game.

The game brought a different type of player to chess. By deploying teams these new winners harnessing AI knew how to use it to analyse their games and to find the best moves whilst they focused on the long game — strategy.

Strategy, involves emotions, though some CEOs will say that needs to be removed from the decision making. HBO’s fictional drama Succession, lays it all out. And Moravec’s paradox tells us computers are crap at emotions. Cue Star Trek Data’s emotion chip.

Another simple way of explaining strategy would be for me to decide what I wanted to write in this article and why ( strategy) and have Google Bard write it. But, and this is the but, I may even likely alter the text because it lacks that something, based on mine, or in your case your super power.

Success for chess and its players then? However there’s a catch! What do chess, football, Journalism, and many other professions have in common with each other? Generally they’re based on cognitive patterns in ‘narrow worlds’ that are discernible and can be replicated for solutions. Hence the more experienced you are, generally the better you are at solving these problems.

Narrow worlds point to specific domains which operate under codified guidelines. The term was coined by John McCarthy in his 1956 paper, “Programs with Common Sense” about AI solving domain specific problems..

Problem solving based on “narrow worlds” deploying experienced hands has been the accepted thought process that nominally has served society well. But there’s a false premise lurking in this the world we inhabit today, and with AI in our shadows.

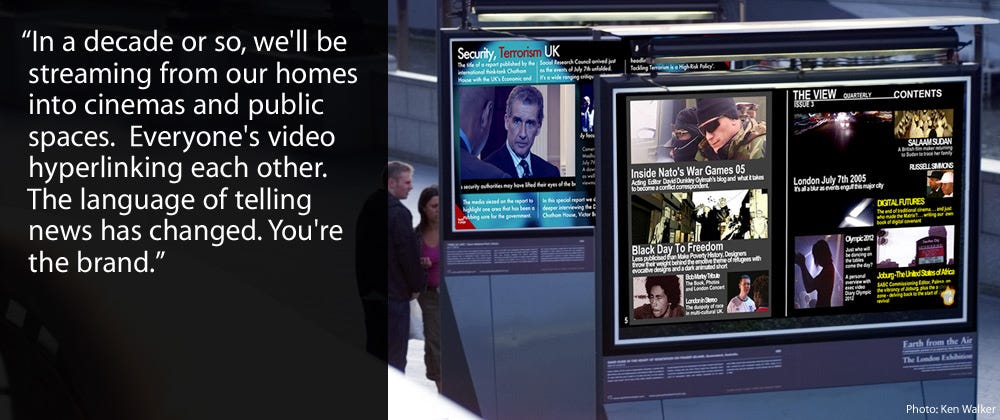

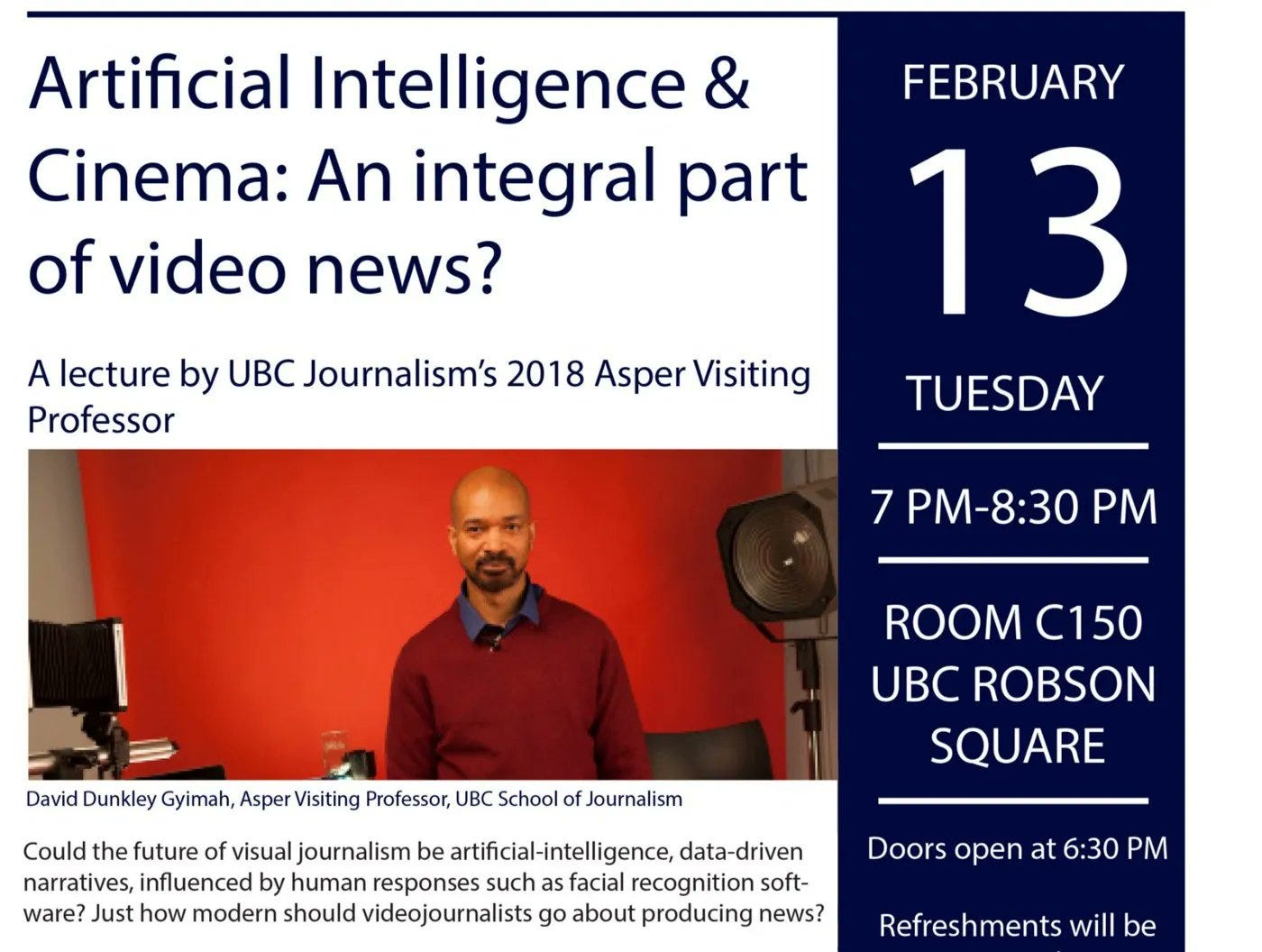

For the last twenty odd years I’ve been teaching and training cohorts in computational, design and behavioural skills. That was rebooted in 2016 as the Digital Lab, and 2019 when, with a colleague, we launched Emerging Journalism, or as like to call it Applied Storytelling or the LAB.

An observation of students who take that elective tend to have a range of interests, from music, games, art, language and in some cases have n extraordinary super power in which they have an extraordinary gift for visualisation over words. That’s not to say they can’t or won’t write — some have gone on to become editors of national newspapers.

Yixiang, was a formidable concert player. She hid that from us, but there was a different quality to her work which when I questioned she revealed this. She’s now a senior financial journalist.

It’s more how they’re able to express themselves and see the world differently. My job at the lab is to enhance that, and my colleague and I do so by collapsing several, oft unrelated disciplines that impact thinking.

Almost all students come to the lecture with an idea and by our third lab start to turn on themselves and express their super power. How to solve a problem first guided by some expression, but by not being conventional. In fact the key statement is diversity.

No, wait, wait! For that brief moment, you might have thought “oh yeah right, I see!” Diversity here envelops culture, thought, hobbies, your life outlook, approach to problems.

Your super power is based on diversity of being and thought et al. The more different you are, and aren’t we all different, the more your super power for problem solving comes into play. In fact, the definition of the word super power is really your uniqu power. Super power is to think diversely.

Another observation from years of interactions, teaching and training is how diversity of thought within a homogenous group is different from that in a heterogenous group. It’s the unpredictable vs the crowd solution. And that’s not say the crowd solution isn’t right; of course it is and will be. But the expressive collective approach from the unknown is a super power, and one that AI will struggle to capture.

So how do you get there? Self nurturing. The students I first see already posses what philosopher Isaiah Berlin called Fox qualities. These are individuals that delve into many things. They realise the procedural and come to assess conceptual frameworks for dealing with issues.

Journalism isn’t writing, it’s problem solving and in an AI rich world, that added quality for the next gen is to harness the many discursive approaches emerging. In our lab for journalists we refer to them as Applied Storytellers for the application of a host of solutions towards creativity.

In many ways this approach makes sense. The problems that have beset us from old have relied on tried and tested, formats from another generation, a chess board in which the play is determinable from set patterns.

We tacitly and expressively know some of these approaches don’t work. Our attempts at addressing them have been swiped by old hands we deign know best. But these problems are still there. They are wicked problems that require innovative approaches, not for the sake of them, but now, this time, what AI will do.

To make a big thing of it, there needs to be a bigger discussion across disciplines and institutions. This is what my students say of the programme we run below. I’d like to have that massive discussion.

NB: If you’re a TV network we’ve devised an international game that we think is pretty amazing. It’s not unlike the reality game Physical: 100 and one I was involved in as editor for Nato’s War Games. Most images in this article were AI generated.

—

Here’s my scoping of my super power = diverse thinking. I’m British and Ghanaian. I grew up in Ghana, attended Prempeh College (Ashanti King Prempeh II’s college), I graduated in Applied Chemistry at Leicester, studied modules in Global Finance at LSE, then became a journalist.

I became an artist, and artist in residence at the Southbank Centre, hired by Jude Kelly CBE. My PhD from Dublin covers cognition and storytelling. I read several books a year. I’ve travelled and taught in Russia, China, India, Egypt, Ghana, South Africa, Canada, US, across the UK and Europe.

A lecturer at uni who worked in the health system and had knowledge of the ff said I had dyslexia, for the way I processed information. True or not, it’s never been a weight. You can read more about my background here