The frenzy during its launch both excited and terrified the media. A bunch of twenty somethings were about to be unleashed and they possessed something of the dark arts of television.

They could do just about everything that needed done by specialist in news gathering. Today, no question they would be data genies, SM specialists and television-journo-scientists.

It wasn’t about what journalism was as whatever they required outside of it to give it a boost, both in the storytelling and blurring the lines of disciplines.

Backed by tens of millions of pounds and one of the UK’s most respected media moguls, Sir David English, who adopted a hands off approach, every mogul from around the world worth their salt would visit the station to see them, and the equipment at work.

Before YouTube was conceptualised, the station ran a programing schedule controlled from a PC which automatically cued the news like a Juke box. IThey were also the first in Europe to transmit live on the web.

This is the story, you’ve never heard. It’s not alone, as you may be able to recount innovations you know of that should be heard, but this is one of them — Innovation at its zeitgeist. And how the idea lived, died with the closure of the station, and its legacy lives on. That legacy has a currency for television today and the role universities could play.

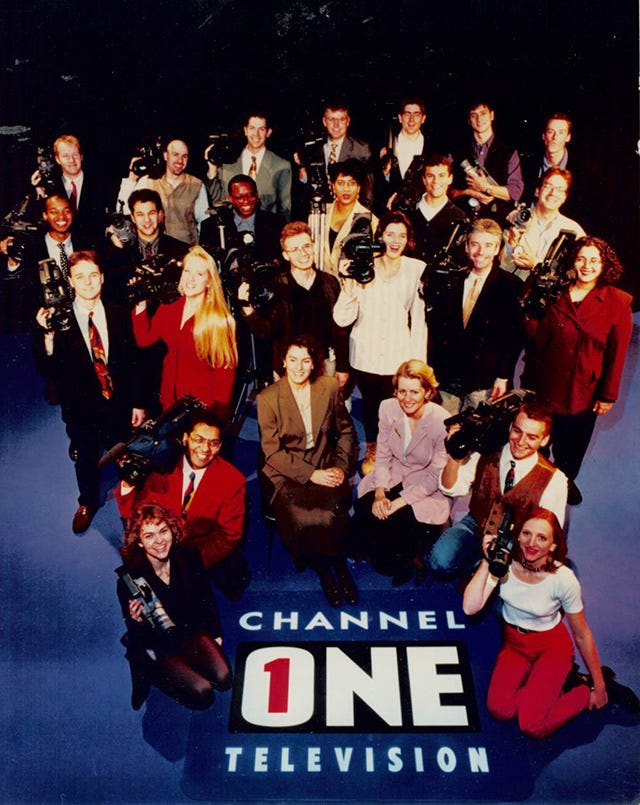

I’m David. I was one of the group (2nd row, 1st left picture) — chosen with thirty journalists from three thousand candidates. Before that I worked on one of the BBC’s most innovative current affairs programmes, BBC Reportage,in Apartheid South Africa eventually reporting Mandela’s inauguration and then working for Channel 4 News and Jon Snow.

In 2005 I became the first Brit to win the coveted Knight Batten Award for Innovation in Journalism, and have lectured (as a visiting professor) and taught innovation around the world e.g. Russia, China, and Africa and presented at places like Apple.

In my last post, I spoke about how television journalism generally rarely led in innovations in tech, which was exploited outside. It was very good at adapting external ideas — from cameras, studio settings, satellite transmissions and latterly in online and its use of video players alongside social media. These usually occurred after lengthy considerations. Yet in 1994 — a group of executives stuck their neck out and did something.

Unlike any other news outlet in British television you can mention today, out of the stations thirty journalists, those from Black, Asian or ethnic backgrounds, or that were women was above the average of any mainstream outfit then and today. The stories came from their communities and viewers. It wasn’t uncommon to be walking down the road and have a van driver shout “Oya Channel One”.

They innovated within the story, the way they told the story, and the range the range of stories. Its journalists abandoned the industry’s style by mixing up genres to cinema — the very thing 40 years ago that was abandoned ( see Pt II).

Dimitri Doganis (2nd back row, 2nd from right above photo) was one of the youngest journalists. Today, he’s an Oscar nominated, BAFTA winning filmmaker who founded RAW TV and talks about innovation at Channel One.

I reserve the greatest sense of innovation for the fact this little known outfit Channel One pioneered videojournalism, selfies, multiple storytelling and reality programming.

A decade later that experience and craft skill would lead to me winning the Knight Batten Award for Innovation in Journalism, International Videojournalism Award and other labels.

Many of the gang of thirty continue to make an impact on the industry in one shape or another: Marcel Theroux (back row, 3rd right) makes exemplary documentaries (as does his brother Louis); Rav Vadgama @TVRav ( not in the picture) is the videojournalist/ cameraman/ producer/ director who brings stories with correspondents to Good Morning Britain, Sacha Van Straten @svanstraten to my right is doing amazing things in technology with education, and Rachel Ellison (front row, Left kneeling) is an MBE, having worked in Afghanistan.

That experience combined with my background too as an Applied Chemist, a passion for art (I was an artist in residence at the London Southbank Centre) and deep interest in culture and politics, led to the creation of a media lab, where we (students myself and colleagues) could interrogate media in ways it rarely does.

Generally making sense of media in education and media largely revolves around cognitivism and semiotics — a culturalised system. One is about common sense, the other learned values. But it’s missing something that we introduced into the lab. An insight into what’s happening in our brain during storytelling.

How do words and images shape our behaviour at a cellular level and why are teenagers less interested in say news? Combining cognitivism, behavioural theory, parts of neuroscience, entrepreneurialism and psychology, we enter a new approach to media and one that I believe every training and teaching centre should adopt, and how educating the public could insulate them from “dead cats and squirrels” and spin.

Did you know that even before social media arrived, youngsters would feel restless or watch television for hours, whilst doing their homework, and that as a parent you’d tell them umpeenth times about making up their room?

Generally their lack of interest to character driven films above plots is also a symptom. In her book Inventing Ourselves Professor Sarah-Jayne Blakemore provides some answers. New knowledge in neuroscience shows the prefrontal cortex — the front part of the brain where decision and executive functions take place is still growing — up until around 25 years.

Professor Paul J. Zak’s work includes hacking Oxytocin — a hormone associated with social bonding. He’s been working to understand how stories motivate and says:

...by developing tension during the narrative. If the story is able to create that tension then it is likely that attentive viewers/listeners will come to share the emotions of the characters in it, and after it ends, likely to continue mimicking the feelings and behaviors of those characters.

Whilst a paper I delivered on Memory which included talking to a former colleague of mine Professor Catherine Loveday narrative she says:

A news story is a shorter piece of information. It may be something that doesn’t engage you as much and so you don’t pay too much attention to it. More importantly it hasn’t necessarily got a narrative that runs through it. So you don’t invest in the story psychologically or immerse yourself the same way you would a film in which you’re relating to the characters integrating it with your own knowledge base and experience.

It’s perhaps early days for factual storytellers and news, but fictional storytellers have been aware of the psychology and neuroscience for a while. Perhaps it’s about time all journalism students should as well.

Author Dr David Dunkley Gyimah is a winner of the Knight Batten Award for Innovation in Journalism, and National Union of Students Teaching Award. He’s a former BBC Newsnight, Channel 4 News and BBC World Service Journalist, whose work is featured in several academic books